The writer's brain unraveled: On writing and thinking

I've been reading a lot of writing by writers lately. Most recently, I enjoyed a post by a prolific blogger and Twitter-er, Chris Brogan, called "Cultivating a Writing Habit" and I chased that shot with an equally inspiring elixir -- a post by my friend Beth about Creative Writing Under Pressure.

Maybe it's just me, or maybe it's all writers in general, but there's something about the process of writing that I find fascinating. Thinking about writing leads to thinking about thinking. And when others talk about writing -- about their own personal writing habits and rituals -- I learn a little something about how they work and how their brains work.

Chris Brogan's brain does not work like mine. He can apparently sit down at any moment, rip open an ink-filled vein, and let words spill all over the pages without feeling a lot of pain.

Beth's brain works a lot like mine. It's kind of like a cat. If I want to have a good experience writing, I have to convince my brain that it is writing because it wants to write. You can't force a brain like mine into doing any writing that it doesn't want to do and expect anything less than a painful outcome. And who wants to write when the fur is flying and the claws are out?

Beth's blog explores some of the ways that she prods, cajoles, tricks, and negotiates with her cat-writer brain. She does other things and waits for the ideas to come to her. Make no mistake, that girl can write on a deadline, all right -- I saw her do it plenty of times in college. But that kind of writing just isn't the same as the kind of writing that comes from a brain that tells you it wants to write.

I am the same way. I wait for the ideas to fall from the heavens and spend afternoons chasing after them with a butterfly net. I usually catch enough to start most any assignment. But when I'm forced to write and I have little inspiration, I turn to reading to jump-start my brain.

Chris Brogan and I are alike in that way. He loves to read. And he is absolutely right that great writers are even better readers. I especially love to read writing by writers for writers.

Good writing is a relief to read. Great writing is fun to read. But brilliant writing -- poetry and prose for true logophiles - that sings to a different part of my soul. I'm talking about writing like you'll find in Catch-22, a book so loaded with irony that it spills right over into the sentence structure.

One of my favorite writers is William H. Gass. His essays are not for the faint of heart. They are intellectual beefsteaks - chewy, delicious, time consuming and worth the effort. I stumbled across his writing in Harper's, where I read his essay "In Defense of the Book: On the Enduring Pleasures of Paper, Type, Page, and Ink" and nearly wept with joy at the exercise (indeed, folks like Stephen Schenkenberg have rightfully credited Gass with turning reading into an aerobic activity).

After reading that essay, I marched right out and bought his book "Tests of Time," a collection of essays that, for me, are roller coaster-ride thrilling to read -- better, actually, because the ride lasts a lot longer, and there's no line to wait in if you want to read the ride again. When I'm in the middle of one of his essays, I can't help but marvel at his skill. I also can't help but think, "My God, how does this man's brain work?"

I've often wondered about his career as a writer. Did William H. Gass perform well under pressure? Did he relish the fast pace of a deadline-driven world, or did he prefer the more organic approach like my friend Beth and I do? Or, did it matter either way?

In my other life as a professionally trained, practicing journalist (in the early 90s) I performed well under pressure. I could negotiate deadlines with ease (I was late in every other area of my life, but I got my copy in on time, most of the time). I eventually discovered my limitations. I discovered the point at which the pressure and stress of a job could be too great - and it would affect the end-product of my writing.

I was a speechwriter for Laura Bush and I worked for the White House on 9-11. An already stressful job became enormously difficult in the aftermath. I was shell-shocked and probably suffered from PTSD for some time after that (remember D.C. had the anthrax scare and the snipers around that same time).

In the midst of all that chaos and terror, I had a difficult time crunching data, processing complex ideas, remembering details, and producing thoughtful, clear, original speeches. Working under such pressure had a profound impact on my writing ability and productivity. Writing a speech was like giving birth - agonizing, painful and ultimately exhausting.

I remember one particularly bad day I was researching a speech, and I was looking at a page of printed type when I realized that I had lost the ability to read. I knew that there were words on the page, but I couldn't tell you what they meant. I was literally dumbfounded. I got up and left my office.

I rarely left my desk when I was working on a speech, but that wasn't by choice. There were too many demands that kept me in my chair, on the phone, or at the computer, and I could rarely get away and find a peaceful place to think and write. Usually a short break would give me just enough energy to finish a job. But that day I just shut down. I had to go home and rest for a few hours before I could read and write again.

It took several years to mentally unwind after I left the White House. Whenever I was presented with an important or complex writing job, I had to slog through it -- coaxing, cajoling, tricking, and finally flat-out forcing my brain to think, think, think. I wasn't pleased with any of my work. It was adequate but not inspired.

Writing - the one thing that I loved most in life; the thing that had been therapeutic and inspiring since childhood - drained me. My brain was empty and silent. I wasn't sure if I would recover that joy again, but I did, thank God. The internal dialogue came back, one word at a time. I found inspiration in reading. In writing poetry. In writing for myself instead of someone else. In not forcing it, but allowing it to rain down on me. The old cliche is true. Time does heal most wounds.

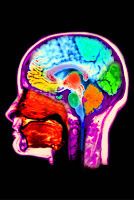

The brain is a fascinating thing that we are only now beginning to peel apart and understand. From what I've gathered over years of reading about early childhood cognitive development, psychology, and current research about the brain, in some patients with PTSD or depression, the amygdala (the "fight or flight" center of the brain) often usurps the

hippocampus -- the amygdala's next-door neighbor that controls learning and recall (memory). It essentially dampens the sort of creativity we need to develop unique ideas and write beautiful sentences.

hippocampus -- the amygdala's next-door neighbor that controls learning and recall (memory). It essentially dampens the sort of creativity we need to develop unique ideas and write beautiful sentences.Yet the amygdala is also responsible for what's called "fear" learning

(coping skills, reactions and/or responses to danger). So, on the one hand, stress and fear inhibit cognition but might promote a specific kind of creativity: e.g. problem-solving skills necessary to save a life or preserve a species. Does that mean writing on a deadline triggers fear-based cognition, and pleasure writing is an entirely different cognitive process?

For that answer I turned to someone I recently discovered on Twitter, Dr. Ellen F. Weber. Dr. Weber is CEO and President of MITA International Brain Based Center for Renewal in Secondary and Higher Education, and an author, lecturer and columnist. She said, essentially, that "Stress shuts down learning, lowers (immunity), blocks growth, limits creativity and adds the toxic chemical cortisol (to the brain equation). Relaxed writing generates serotonin, fosters curiosity, draws from multiple intelligences, and grows brain cells for solutions."

I'm fascinated about studies that explore how the stress, fear and rage responses impact creativity, learning and memory in people with depression, anxiety disorder, or PTSD (patients who are assumed to have hyper-sensitive fear or rage responses as a result of some past or recent trauma).

For example, a recent study in Michigan is exploring the effects of cannabinoids on the brain (as in cannabis - marijuana - THC). I learned that the part of the brain with the greatest number of cannabinoid receptors is the amygdala (fight or flight center). I also learned that our bodies actually make a version of this substance - called, appropriately, endocannabinoids. Who knew that the human body was capable of producing its own brand of THC.

Funny, yes, but think of the implications and contradictions. On the one hand, people with depression or PTSD have trouble remembering things and/or processing complex data. In those patients, brain scans reveal overactive amygdalas that are often deteriorating -- possibly due to the toxins produced from stress (like cortisol). On the other hand, potheads have trouble remembering things or processing complex data too. But what happens if you give stressed, anxious or depressed patients cannabinoids? Early research seems to suggest that they might just relax and think things through.

Wait a second.

Most research seems to show that THC has a detrimental impact on memory function. But if those same substances have been shown to dampen the emotional responses that interfere with learning and memory, then is it hypothesized that cannibinoids have potential benefits in patients with PTSD/anxiety disorder -- and might somehow actually help promote learning and memory? Is this the scientific equivalent of writing on Beth's deadlines versus Charlie's vacuum-the-house-generated prose?

I'd like to see brain scans of writers writing under the following conditions: on deadline, with someone screaming at them, after cleaning house or driving a car or other idea-generating activities, after jogging and after being given THC.

Could we see the actual changes in cognition? What parts of the brain would light up or turn off? What could we learn from this sort of study? And how would that impact the blogosphere and newsrooms across America?

Wouldn't you just love to peer inside the brains of your favorite writers and see not only what makes them tick, but also how they tick?

Any volunteers?

Labels: Beth Zesinis, brain, brain research, Catch-22, Chris Brogan, cognition, creativity, memory, research, White House, William H. Gass, writers